The greatest explosion in the history of entertainment and the cult of celebrity was captured in exhilarating new art forms by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901) in the Parisian district of Montmartre at the turn of the 20th century. Toulouse-Lautrec and Montmartre was organized by the National Gallery of Art, Washington, where it was on view in the East Building, March 20 through June 12, 2005, and by The Art Institute of Chicago, where it was presented July 16 through October 10, 2005. More than 240 works created primarily by Toulouse-Lautrec include paintings, drawings, posters, prints, sculptures, zinc silhouettes from the Chat Noir shadow plays, and printed matter such as illustrated invitations, song sheets, advertisements, and admission tickets. Toulouse-Lautrec's predecessors Edgar Degas and Edouard Manet; his contemporaries Pierre Bonnard, Vincent van Gogh, and Pablo Picasso; and poster artists such as Jules Chéret were also represented.

TOULOUSE-LAUTREC

Toulouse-Lautrec, a patron of the celebrated Moulin Rouge music hall, defined Parisian life of the 1890s with his colorful images of the characters who filled Montmartre's dance halls, bars, cabarets, cafés-concerts, and brothels. He was born into a provincial aristocratic family and arrived in Paris in 1882 for training as an artist. He preferred the gaudy, vulgar, somewhat disreputable milieu of Montmartre to the world of his own social class. His professional career began around 1891 when his first poster featuring La Goulue (the stage name of Louise Weber) performing the cancan hit the streets of Paris.

Toulouse-Lautrec was one of the greatest printmakers, and his color lithographs are known for their sophisticated and innovative technique. The artist is still admired for his bold use of color and striking design as well as the distinctive imagery found in his posters of Montmartre's cast of characters.

At the turn of the 20th century, Montmartre had many dimensions and meanings. It was a physical location, a part of Paris, a social environment with its own populations, class structure, and economy. It was also the hub of an entertainment industry, as well as the nerve center of an avant-garde culture that not only appeared in literature, performance, and the visual arts, but also was a frame of mind. Much of Montmartre's excitement at this time came from such activities as satires and performances that tested the limits of the cabarets and café-concerts, and bawdy displays in the dance-halls. This critical and anti-establishment milieu challenged the values and morals of the Third Republic.

EXHIBITION: Organization

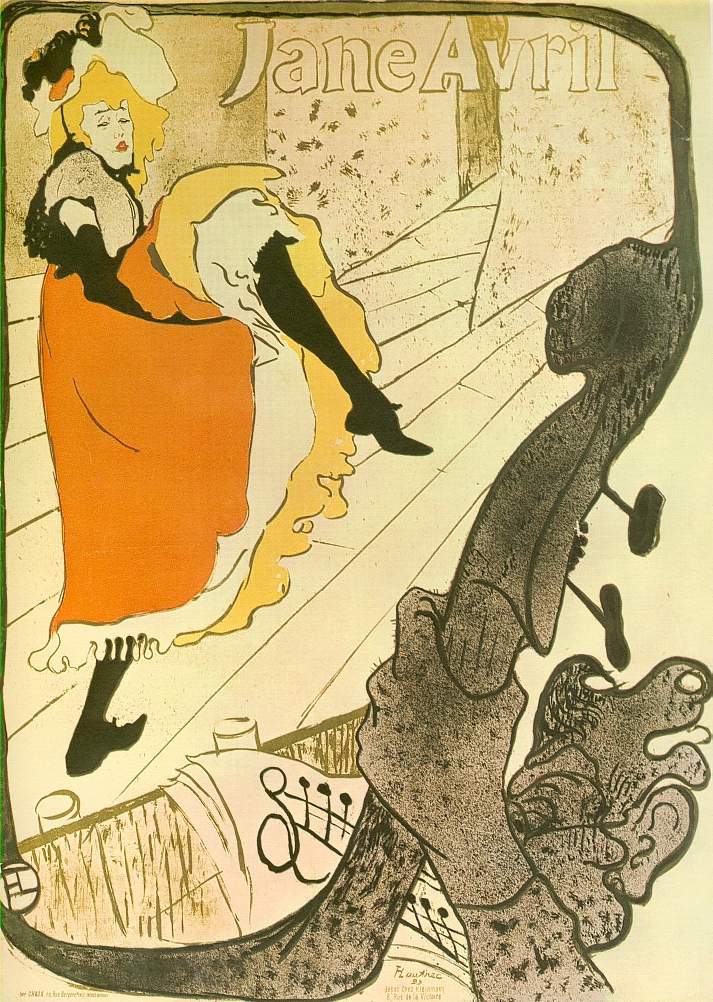

Works by more than 50 artists were arranged thematically, focusing on the many components of Montmartre's nightlife. The exhibition was dominated by Lautrec's celebrated posters and many of his most striking paintings and drawings of dance halls, cafés-concerts, cabarets and performers such as Aristide Bruant, La Goulue, Jane Avril, Yvette Guilbert, May Belfort, May Milton, Loïe Fuller, and Marcelle Lender. The final section was devoted to the depictions of the circus, a subject that brackets Lautrec's career, from his earliest mature works to a group of late drawings that helped secure his release from involuntary confinement in a sanatorium. The sections of the exhibition were as follows:

Introduction to Montmartre:

_1891.jpg)

A display of posters immersed visitors in the Montmartre milieu, working class neighborhood by day and festive and gaudy venue at night. Laturec's great first poster Moulin Rouge: La Goulue (1891) was seen opposite Jules Chéret's Bal du Moulin Rouge (1889), Maxime Dethomas' "Montmartre" (1897), and Théophile Alexandre Steinlen's La Rue (The Street) (1896).

The Typology of Montmartre:

The next two rooms of the exhibition showcased the stereotypes found in Montmartre such as the couple in Lautrec's A la Mie (1891) and minor celebrities who thrived in the raucous atmosphere of this quartier.

Lautrec depicted fellow artists in Vincent van Gogh (1887)

and The Hangover (Gueule de Bois) (c. 1888), for which Suzanne Valadon posed.

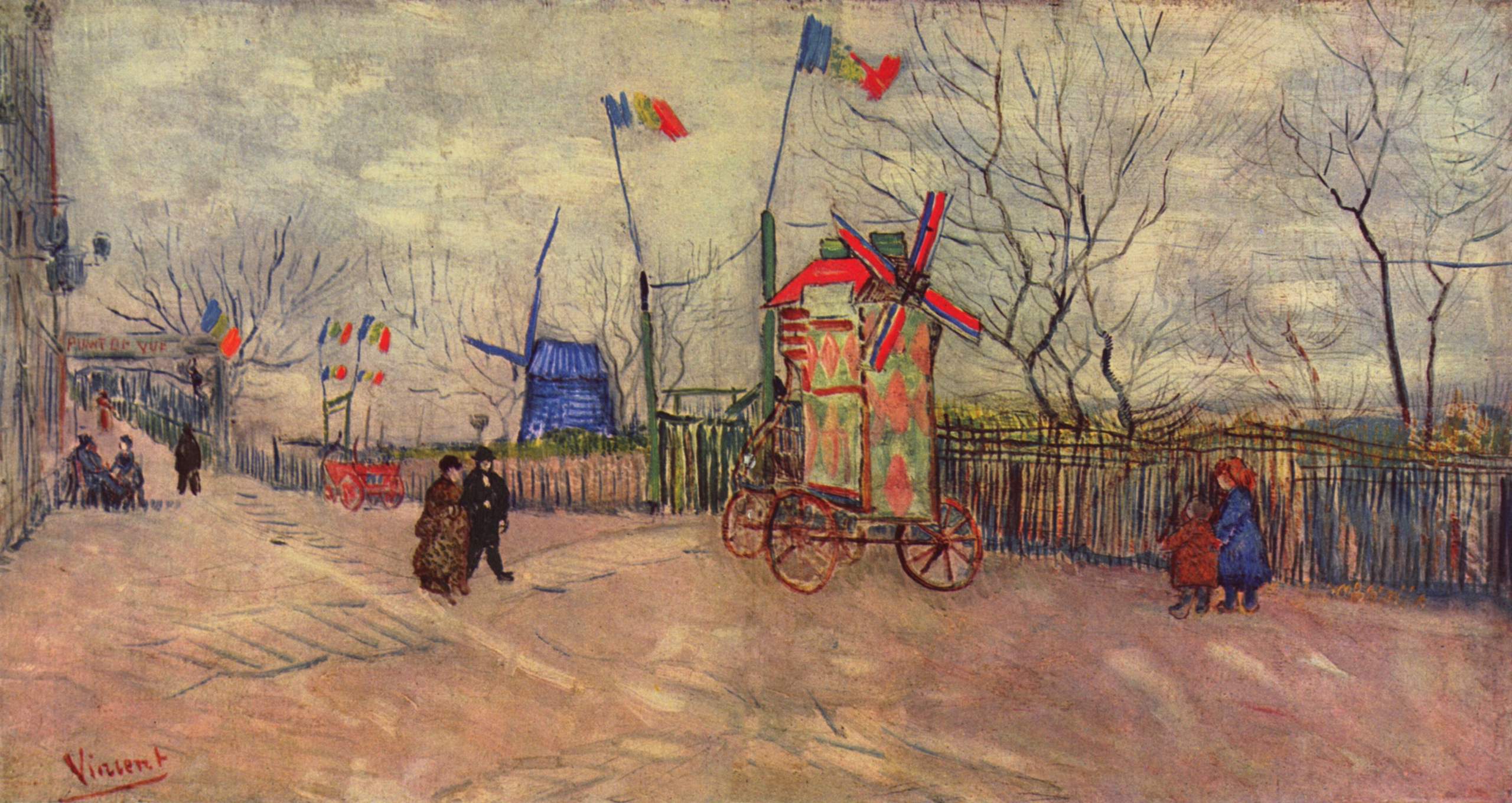

Several works also reveal the cityscape of this Parisian district, such as Vincent van Gogh's A Corner of Montmartre: The Moulin à Poivre (1887)

and Santiago Rusiñol's The Kitchen of the Moulin de la Galette (c. 1890–1891).

The Moulin Rouge and Other Dance Halls:

The paintings that Lautrec made of the dance halls of Montmartre, mainly the Moulin Rouge and the Moulin de la Galette, constituted the majority of his large, multi-figure canvases, in which he demonstrated his compositional skill. In this section of the exhibition, the most famous nightclub in Paris, the Moulin Rouge, was introduced with a wide variety of illustrated invitations, song sheets, and advertisements, which included a photorelief of the club seen in The Dance Hall of the Moulin Rouge, illustration in Le Panorama: Paris la Nuit (c. 1898).

Seminal paintings by Lautrec, At the Moulin Rouge (1892–1895),

Quadrille at the Moulin Rouge (1892),

Moulin de la Galette(1889),

A Corner of the Moulin de la Galette (1892),

and important lithographs, The Englishman at the Moulin Rouge (1892),

and The Clowness at the Moulin Rouge (1897), feature the many patrons and performers of Montmartre at these dance halls.

The Chat Noir and Aristide Bruant:

Rodolphe Salis opened the doors of his cabaret artistique in November 1881 under the name “Le Chat Noir.” The appellation “Black Cat” had a wide resonance, evoking the work of both Charles Baudelaire and Edgar Allen Poe, widely admired by the artistic community at this time. The black cat was often a character in classic French folktales, with simultaneously innocent and sexually provocative undertones. The mixture of history, art, literature, and sexual suggestion implied by the name suited Salis’ intentions perfectly, and the black cat, with all its innuendo, became an enduring symbol of Montmartre.

Salis and his group of talented writers, poets, artists, and singers created a specifically Montmartrois performance and experience that drew audiences throughout Paris. The Chat Noir became known for a type of shadow play, which used zinc cutouts against artfully lighted backdrops, such as Henry Somm's Five Female Figures (1887) silhouette for the shadow play "Le Fils de l'eunuque." The success of this entertainment prompted Salis to take his shadow theater on tour, announced by Théophile Alexandre Steinlen's now-famous poster Tournée du Chat Noir (1896). The adjective “Chatnoiresque” was coined to describe this unique blend of irreverence, humor, and art and was one of the defining attributes of Montmartre culture.

In Steinlen's, Apotheosis of Cats (c. 1890), a massive mural three-meters wide and over a meter-and-a-half tall, cats of all colors perch on rooftops and turn toward a large black cat poised before a full moon. Salis had a keen eye for talent and supported a remarkable group of artists and performers, such as the charismatic and influential Aristide Bruant, who later opened his own club, Le Mirliton. Three large posters of Bruant by Lautrec, advertising the chansonnier and Le Mirliton were included in the exhibition.

The Cafés-Concerts:

Of all the pleasures of Paris—the dance halls, circuses, cabarets, and brothels—it was the café-concert and its stars that cast the greatest spell on Lautrec.

The emergence of the poster as high art could be seen in Lautrec's depictions of two British stars, May Milton (1895) and May Belfort (1895).

Other renditions of the cafés-concerts by Lautrec predecessors and contemporaries are Degas' pastel, Café-Concert (1876/1877) and Vuillard's At the Café-Concert, May Belfort(1895).

Lautrec's seminal painting, Marcelle Lender Dancing the Bolero in "Chilpéric" (1895–1896) was also on view in this section.

Stars of the Café-Concerts:

While attending performances at the cafés-concerts, Lautrec developed what he called furias, intense obsessions with certain performers who would enthrall him for a single season or several years. The artist would return night after night, recording the gestures, facial expressions, and postures that made each performer unique. Lautrec's ephemeral drawings, innovative publicity posters, technically sophisticated prints, limited-edition lithographic albums, fully realized paintings, and his sole ceramic piece, explore the construction of the café-concert star in an array of guises, creating some of the most memorable images of Montmartre's celebrities.

The next two rooms depicted Jane Avril in her iconic black stockings

and Yvette Guilbert in her signature black gloves. There were six small bronzes by Francois Rupert Carabin, 13 of Lautrec's important color lithographs of Loïe Fuller, as well as archival footage of Fuller dancing in one her famous voluminous dresses.

The Maisons Closes: Between the mid-1880s and mid-1890s, Lautrec produced some 50 paintings on the theme of prostitution. The maisons closes as brothels were known under their French euphemism, were discreetly housed, regulated by the police, and their personnel subject to regular medical inspection.

Lautrec closely observed the women of these houses and depicted their activities frankly, such as the women awaiting clients in In the Salon: The Sofa (c. 1892–1983).

Earlier and later artists were also fascinated by the maisons closes. During the later 1870s, Edgar Degas had made about fifty monotypes on this theme, such as Two Women (1876–1877). A 1901 maison close interior, Nude with Stockings demonstrates Pablo Picasso’s take on the stereotype. Toulouse-Lautrec's representations of this nocturnal demi-monde are never sensationalized, instead he views the cast of characters with a profound human sympathy.

The Circus:

One of the great spectacles of the 19th century, the circus combined extraordinary gymnastic and acrobatic feats, animals trained to obey and amuse, clown comedians, and control and chaos. As an important part of the entertainment industry, the circus relied on both tradition and expectation, in addition to innovation and novelty, as did the dance halls and the café-concerts. The circus was deeply ingrained in Lautrec’s imagination, and he knew the world of horses from his aristocratic childhood.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, At The Circus Fernando, 100.3 x 161.3 cm, 1888

Lautrec's early depictions of the circus in the late 1880s

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, At the Circus: Horse Rearing, 1899

differ dramatically from his later depictions, when he was forcibly hospitalized for his alcoholism. Desperate to demonstrate his improvement and speed his release, he produced a poignant series of drawings on circus subjects, where combinations of fantasy and reality recall the graphic work of Francisco Goya.

CURATORS AND EXHIBITION CATALOGUE

Richard Thomson, Watson Gordon Professor of Fine Art at the University of Edinburgh, distinguished historian of French 19th-century art and co-curator of the Toulouse-Lautrec retrospective exhibition held in Paris and London in 1991, was guest curator of Toulouse-Lautrec and Montmartre. The exhibition was overseen in Washington by Philip Conisbee, senior curator of European Paintings, as well as Florence E. Coman, assistant curator of French paintings, and from the Art Institute of Chicago, the exhibition was supervised by Douglas Druick, Searle Curator of European painting and Prince Trust Curator of Prints and Drawings, and Gloria Groom, David and Mary Winton Green Curator of European painting.

Thomson was principal author of the catalogue. Phillip Dennis Cate, director emeritus, supervisor of curatorial and academic activities, The Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, and Mary Weaver Chapin, Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Curatorial Fellow in the department of European painting at the Art Institute of Chicago, contributed essays to the catalogue, published by the National Gallery of Art in association with Princeton University Press.