The Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University presented American ABC: Childhood in 19th-Century America, one of the most comprehensive art exhibitions in recent decades to deal with American childhood, from February 1 through May 7, 2006. The exhibition, which featured paintings by Winslow Homer, Thomas Eakins, George Catlin, Eastman Johnson, and other celebrated American artists, premiered at Stanford then traveled to the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C., July 4-Sept. 17, 2006; and the Portland Museum of Art, Portland, Maine, Nov. 1, 2006-Jan. 7, 2007.

Presenting paintings, prints, photographs, and books selected from major museums, libraries, archives, and private collections throughout the United States, American ABC explored the connection between images of the American child and the democratic ideals of the young United States. The exhibition also included a wide variety of illustrated children’s books, such as Mark Twain’s Huck Finn, Noah Webster’s Elementary Spelling Book, McGuffey’s readers, and colorful ABC primers.

Over the course of the 19th century, the United States grew from an infant republic to a powerful nation with a prominent place in world affairs. American ABC demonstrates how portrayals of the nation’s youngest citizens took on an important symbolic role in the United States’ long journey towards maturity and will provide a window into the everyday life of the period--the world of families, children’s pastimes, and the routines of the schoolhouse.

The exhibition's companion book, published by Yale University Press, expands on the themes of the exhibition and presents new research on the social and economic significance of childhood in 19th-century America.

Thomas LeClear, "Interior with Portraits", circa 1865, oil on canvas, 25 7/8" x 40 1/2". Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C. Museum purchase made possible by the Pauline Edwards Bequest.

Winslow Homer (1836-1910), Snap the Whip, 1872. Oil on canvas. 12 x 20 inches. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Gift of Christian A. Zabriskie, 1950.

Thomas Eakins (1844-1916), Elizabeth with a Dog, circa 1871. Oil on canvas, 13-3/4 x 17 inches. San Diego Museum of Art, California. Museum purchase and a gift from Mr. and Mrs. Edwin S. Larsen.

From Antiques and Fine Art:

Winslow Homer (1835-1910), The Watermelon Boys, circa 1876. Oil on canvas, 24-1/8 x 38-1/8 inches. Cooper Hewitt, National Design Museum, Smithsonian Institution, New York. Gift of Charles Savage Homer, Jr.

This work is one of several by Homer that explored the situation of African-American children in the postwar environment. This painting takes the subject of black children adapting to new circumstances one step further, showing a pair of black boys in an easy friendship with a white companion. The three youngsters feast on fruit, a theme that was ubiquitous in nineteenth-century representations of the country boy.

The watermelon had functioned as an emblem of blackness in the United States since the first half of the century, and it featured prominently in racist depictions that proliferated after the Civil War. Although the watermelon was an icon of racism, the inclusion of the white child in the group raised the work above the level of mere stereotype. The painting boldly introduced the concept of racial integration, an issue that was a minefield of controversy in the postbellum period. Setting the scene in the realm of childhood, however, disconnected it from prevalent fears about interracial marriages, the potential for black domination of the labor market, and other scenarios that played on white imaginations in the postwar period. The verdant scene is Eden-like, with the fruit they share symbolic of an impending fall from grace. Sitting next to a long fence that bisects the landscape, the white and black boys who are "going halves" on the watermelon will grow into manhood in a society divided along racial lines.

Grace Carpenter Hudson (1865-1937), Little Mendocino, 1892. Oil on canvas, 36 x 26 inches. California Historical Society, San Francisco.

Francis William Edmonds (1806-1863), The New Scholar, 1845. Oil on canvas, 27 x 34 inches. Manoongian Collection, Detroit, Michigan.

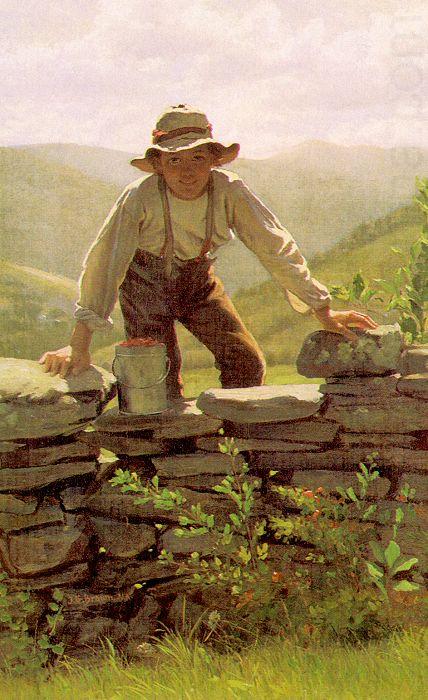

John George Brown, The Berry Boy (circa 1875)

George Catlin, Osceola Nick-a-no-chee, A Boy (1840)

William Bartoll, Boy with Dog, circa 1840-1850, oil on canvas, 30 1/4 x 24 1/4 inches, Greenfield Village and Henry Ford Museum, Dearborn, Michigan

Seymour Guy, Unconscious of Danger, 1865, oil on canvas, 20 x 16 inches, private collection

Eastman Johnson, The Party Dress (The Finishing Touch), 1872, oil on composition board, 20 5/8 x 16 11/16 inches, The Wadsworth Athenaeum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut, Bequest of Mrs. Clara Hinton Gould

Cornelia S. Pering, Little Girl with Flowers (Emily Mae), 1871, oil on canvas, 46 1/2 x 37 inches, private collection

From Stanford Report (images added):

The exponential growth of American cities, which by mid-century were overcrowded with unskilled immigrants, gave rise to the images in the "Ragamuffins" section. Jacob Riis' photographs of ragged children sleeping over grates in the streets of New York in the latter part of the century shows the degradation of the urban poor.

Eastman Johnson, Ragamuffin, circa 1869, oil on canvas, 11 1/2 x 6 3/8 inches, private collection

The exhibit also offers sunnier depictions, like those of spunky "newsboys," who were conceived as poor "go-getters" on their way up.

Henry Inman's News Boy, 1841,

is leaning insouciantly on the stairs of the Astor Hotel, the most luxurious in New York. "There is this idea that even though he is a newsboy today, soon he will be walking up those stairs…"

The 19th-century belief in the transformative power of education is exemplified in

Eastman Johnson's Boyhood of Abraham Lincoln,

which depicts a young Lincoln, his face glowing, reading before a fire. The painting was created in 1868, following both Lincoln's death and the Civil War, which had claimed the lives of 600,000 Americans. "There was a terrible sense of the loss of innocence, of having made mistakes that were unforgivable, final, indelible." Just at this low ebb, "this image of young Abe surfaced as a reminder of the Founding Fathers' advice about 'correct nurture.'

Interesting review (in addition to the two cited above):

http://www.artblog.net/post/2006/11/abc/