On Feb. 27 2004 the Smithsonian American Art Museum opened "Treasures from the Smithsonian American Art Museum," an installation of some of its greatest paintings in the Grand Salon of its Renwick Gallery. This striking selection of more than 185 works were hung salon-style, one-atop-another and side-by-side to re-create the elegant setting of a 19th-century collector's picture gallery. This installation remained on view through 2005.

The works in this installation were selected from four strengths in the museum's permanent collection: Colonial and Federal artworks, American impressionism, Gilded Age treasures and art of the Western frontier including the Taos School.

The earliest paintings in this installation were from the time when the Colonies were transformed into a nation. These rare artworks by John Singleton Copley, John Trumbull and Charles Willson Peale displayed the growing self-awareness and optimism of the new nation. Other works included still lifes by Raphaelle Peale and Severin Roesen, and landscapes by Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand. This section of the installation also included Robert Scott Duncanson's view of a peaceful rural paradise,

"Landscape with Rainbow" (1859),

and Frederic Edwin Church's dramatic landscape

"Aurora Borealis" (1865).

Impressionist artists included in this installation, such as Childe Hassam:

Improvisation (1899)

John Henry Twachtman, William Merritt Chase, and Thomas Wilmer and Maria Oakey Dewing, often worked outdoors to capture brilliant effects of light and color to create luminous paintings.

Other artists whose works were included in the Grand Salon and display the freedom and sparkling qualities of the new impressionist style are Theodore Robinson, Mary Cassatt, Willard Metcalf and Henry Ossawa Tanner, who borrowed the French painter Claude Monet's signature subject for his own

"Haystacks" (about 1930).

Artists who painted during the last quarter of the 19th century, dubbed the Gilded Age by Mark Twain in 1873, captured the brilliance of turn-of-the-century society and a new current of sophistication in America. Artworks by some of the most important artists of the day such as Winslow Homer:

High Cliff, Coast of Maine (1894)

John Singer Sargent (below)

and Albert Pinkham Ryder:

The Flying Dutchman (about 1887)

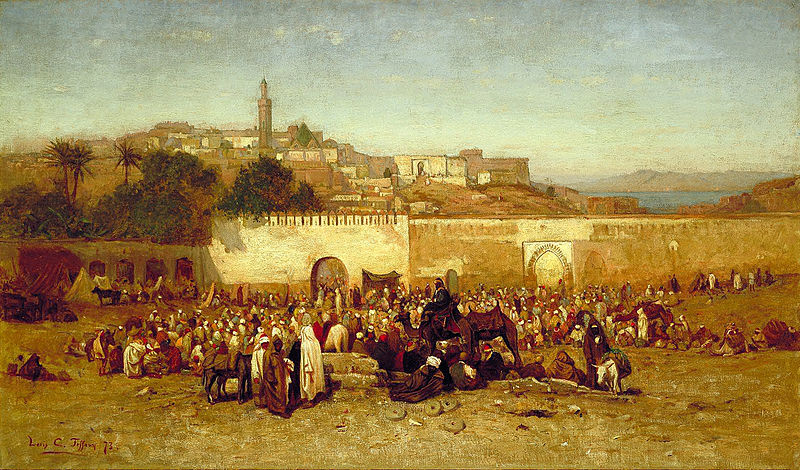

were in this installation. Artists at this time were fascinated with exotic cultures, as seen in

Louis Comfort Tiffany's "Market Day Outside the Walls of Tangiers, Morocco" (1873)

Frederick Arthur Bridgman's Oriental Interior (1884) and

and H. Siddons Mowbray's "Idle Hours" (1895).

Also on view was Abbott Handerson Thayer's ever-popular

"Angel" (1887).

The three monumental landscapes by Thomas Moran

"The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone" (1872),

"The Chasm of the Colorado" (1873-1874)

and another view also titled

"The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone" (1893-1901)

remained on view in the Grand Salon. The two earlier paintings were on long-term loan from the U. S. Department of the Interior. Moran's western landscapes inspired Congress to establish the National Park Service and set aside Yellowstone as the country's first national park in 1872.

Other Western works on view are 29 portraits of Native Americans and scenes of Plains Indian life by George Catlin, who followed the path of explorers Lewis and Clark, traveling up the Missouri River into the Dakota Territories in the 1830s.

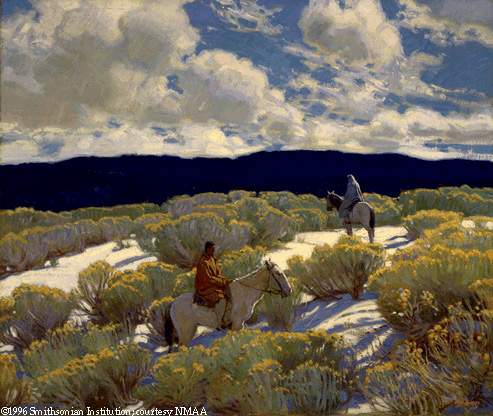

Victor Higgins, Joseph Henry Sharp, Ernest L. Blumenschein and several other artists in the installation were part of the Taos School, begun informally in the 1890s when artists visited the Southwest as an antidote to urban industry and the sophistication of Eastern cities during the Gilded Age. Their bold compositions, as seen in E. Martin Hennings's

"Riders at Sunset" (1935-1945),

used strong color and bright light to depict this region.

The nearby Octagon Room showcased works from the late 19th and early 20th century by artists such as Thomas Wilmer Dewing, Albert Pinkham Ryder, William Glackens, Maurice Prendergast and John Ferguson Weir that are also hung salon-style.

In the adjoining hallway,

John Singer Sargent's "Elizabeth Winthrop Chanler (Mrs. John Jay Chapman)" (1893),

Cecilia Beaux's "Man with the Cat (Henry Sturgis Drinker)" (1898)

and Robert Henri's "Portrait of Dorothy Wagstaff" (1911)

were among the portraits on view.

_________________________________________________________________

More from the Gilded Age::

The intimate world of women and children at home, seen in

An Interlude (1907) by Sergeant Kendall, offered a comforting refuge. Yet danger could invade even the sanctuary of the home, as portrayed by

J. Bond Francisco in The Sick Child (1893),

in which a mother keeps watch as her son hovers between life and death.

Artists and their patrons shared an ambition to present American civilization as having grown past its earlier provincialism to full maturity, equal to Europe's much-admired culture. Evocations of music abounded, as in

Thomas Dewing's allegory of Music (about 1895), where a prevailing gold palette evokes a musical tonality.