Kazimir Malevich – The World as Objectlessness

1 March 2014 - 22 June 2014 | Kunstmuseum

In 1927, the Bauhaus’s publishing arm brought out a book in which Kazimir Malevich, creator of

the Black Square, which has long been an icon of modernism, laid out his vision of the “World

as Objectlessness.” In a carefully orchestrated blend of text and illustrations, the book, which

remained Malevich’s only piece of writing to be published in a Western language in his lifetime,

entices the reader into a world beyond the visible, though the approach is initially far from

straightforward. Starting with the square—at first glance, a simple, even almost banal image—

Malevich elaborates the Suprematist vision of a world in which nothing but pure sensation

prevails. Once the sensation that has temporarily come to rest in the square is set in motion, a

circle emerges; division yields a cross or a rectangle; more complex forms evolve to render the

sensations of flight, flow, magnetism, or the universe. Although the titles of the illustrations

relate them to concrete realities, Malevich’s driving purpose was to eliminate any resemblance

with visible things. The Suprematist square—which is actually not a geometrically exact square

but a quadrilateral—manifests this rejection of mimesis.

For the first time in a long while, the Kunstmuseum Basel’s Department of Prints and Drawings

presents the drawings from its collections that served as masters for the book. The

accompanying catalogue, to be published in separate German and English editions, includes a

new translation of the artist’s illustrated essay (earlier German and English translations

rendered the title, less than accurately, as “The Non-Objective World” or “The World as Non-

Objectivity”) and meticulously reconstructs the history of the work’s genesis: when and where

did Malevich create the illustrations and texts, and which moment in his evolution as an artist do

they reflect? Malevich’s World as Objectlessness is thus revealed to be a fluid vision of a world

and a snapshot in time of a boundless artistic universe.

A new translation of Malevich’s Bauhaus publication with extensive commentary on the history of its creation

This volume offers a new translation of the artist’s illustrated text along with fundamental research on the preliminary drawings, now in the possession of the Kunstmuseum Basel, made for the Bauhaus publication. The rigorous exploration of these works of art provides new insight into the history of the creation of the work: when and where were the illustrations done, and which juncture in Malevich’s artistic career do they reflect? Malevich’s The World as Objectlessness is a snapshot in time of a boundless artistic universe. (German edition ISBN 978-3-7757-3730-2)

KAZIMIR MALEVICH AND THE RUSSIAN AVANT-GARDE

The Art and Exhibition Hall of the Federal Republic of Germany, Bonn

11 March – 22 June 2014

Kazimir Malevich (1878–1935) is one of the most influential artists of the twentieth century. In the West the painter, theoretician and teacher is best known as the originator of Suprematism, an art movement based on pure, nonobjective abstraction. But his oeuvre is rooted at the crossroads between abstraction and figuration, between a universal idea of what it is to be human and the declared ambition to create a new world through art. Presenting a wide selection of paintings, prints and sculptures totalling more than 300 works, the exhibition sheds light on the key phases of Malevich’s career, from the Symbolist beginnings through his pioneering abstract works to the figurative paintings of his later years.

Unprecedented in its scope, the exhibition draws on the support from numerous international lenders. It is the first retrospective to present large groups of works from the collections put together by Nikolai Khardzhiev and George Costakis, housed today at the Khardzhiev-Chaga Cultural Foundation / Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam and the State Museum of Contemporary Art, Thessaloniki. The exhibition is prepared in cooperation with the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam and Tate Modern in London.

Catalogue

Images from the exhibition:

Kazimir Malevich Suprematist Painting (with Black Trapezium and Red Square) 1915 Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam

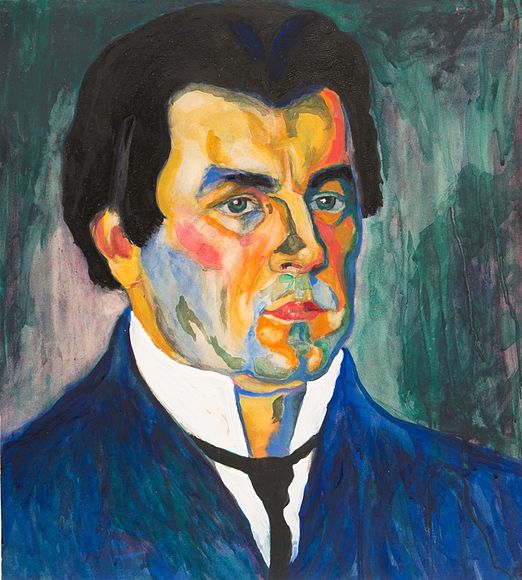

Kazimir Malevich Self-Portrait 1909–1910 Gouache, watercolor and pencil on paper, varnished_European private collection

Kazimir Malevich Self-Portrait 1908–1910 Watercolor and gouache on paper The State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow collection

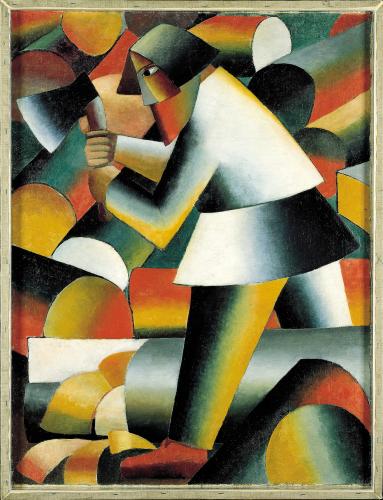

Kazimir Malevich The Mower 1912 Oil on canvas Nizhny Novgorod State Art Museum, Nizhny Novgorod (RU)

Kazimir Malevich In the Grand Hotel c. 1913 Oil on canvas Samara State Museum of Fine Arts, Samara (RU)

Kazimir Malevich Adam and Ewe 1903_Gouache on paper_Vladimir Tsarenkow

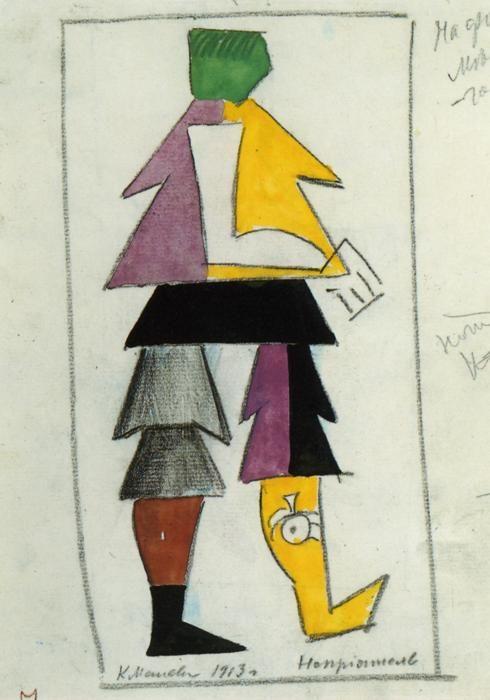

Kazimir Malevich_Costume Sketches for the opera „Victory over the Sun”_Enemy_1913_Pencil, watercolor and Indian ink on paper_St. Petersburg State Museum of Theatre and Music, St. Petersburg

Kazimir Malevich More Costume Sketches for the opera „Victory over the Sun”

Mondrian + Malevich

From 20 November 2003 to 25 January 2004 the Fondation Beyeler presented a series of works by Piet Mondrian (1872-1944) and Kasimir Malevich (1878-1935), two of the fathers of geometric abstraction. Although their paths never crossed and their careers developed quite independently, a comparison was tempting. What Mondrian and Malevich shared in common was a utopian belief in a new, all-encompassing art that would contribute to shaping a new, aesthetic society. While the Russian artist described this faith as “Suprematism, the cosmic union of nothingness and whole,” the Dutch artist christened it “Neo-Plasticism,” a symbol of a universal harmony. Based on a small but significant selection of about 20 paintings each by Mondrian and Malevich, supplemented by a group of drawings, the essential steps in the development of these two pioneers on the path to abstraction are traced.

While Mondrian is well represented in the collection, with seven works that provide an overview of his development, Malevich is one of the “great absentees.” The stature of a private collection derives not only from a consciousness of quality but from a concentration on certain emphases. The pairing of “Mondrian + Malevich” underscores the importance attached to abstract art in the collection, which contains a fine record of three different approaches to non-objectivity in the form of Cubism, the strong presence of Monet’s late work, and the offshoot represented by Kandinsky.

Synthetic Cubism, developed by Picasso and Braque in Paris in 1912, influenced Mondrian in Western Europe, and by way of the Shtshukin Collection, Malevich in Moscow. From this common art historical point of departure, each launched on a completely original path to abstraction. In the exhibition eight pre-Cubist, neo-primitive and Cubo-Futurist paintings reflect Malevich's development. Without first passing through a process of gradual abstraction, Malevich surprised the world in 1915 with the all-negating plane of Black Square on a White Ground. From this elementary form Malevich then derived, through rotation, the circle, then the cross and a range of other shapes, which he placed on a monochrome ground. The exhibition includes a replica made by the artist in 1923 of his triptych of 1915, from the Russian Museum in St. Petersburg.

If Malevich achieved a new level of abstraction by way of a revolution, Mondrian chose a more evolutionary path. In his case, Synthetic Cubism initially inspired a Cubist facetting of the pictorial space. By way of various types of composition which led, around 1920, to a synthesis of line and color field, Mondrian finally arrived at a complete transcendence of subject matter. His pictorial means, reduced entirely to rectangular color fields and straight black lines, now appeared on the painting surface entirely divested of objective reference.

Although both employed a geometric language, Mondrian and Malevich’s compositional principles reflected quite different aesthetic systems. While Mondrian’s solution was line and structure, Malevich selected the plane. In his Suprematist pictures the separate forms seem to hover above the white ground. The effect of Mondrian’s paintings is quite different, every element being locked in a dynamic grid of vertical and horizonal lines. As a result of this grid structure and compositional equilibrium, no element appears in isolation, and every part of the picture is brought into the same plane.

Although there were a number of early Malevich exhibitions, as in Bern, 1959, and Winterthur, 1962, his oeuvre and its links with icon painting were not properly appreciated in the West until the 1970s. The true rediscovery of his late work, which recurred in the late 1920s to objectivity as a result of Stalinist repression, came in the 1990s. It is represented in the present exhibition by a key work, Red Cavalry. Unlike Malevich, Mondrian received an uninterrupted reception that made him a seminal influence on the emergence of a new world art.

Despite the great Malevich retrospectives on tour through Paris, Berlin, New York and Houston, it proved possible to bring works of his to Riehen. The great majority of the Malevich loans on view came from the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, followed by six major works from the State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, one painting from the Art Museum in Tula, Russia. Four Mondrian paintings were provided by the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, two by the Max Bill Estate, and two by the Gemeentemuseum Den Haag, The Hague.

Kasimir Malevich

The Woodcutter, 1912

Oil on canvas, 94 x 71.5 cm

Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam

The catalogue to “Mondrian + Malevich” was published in a bilingual edition (German and English) by Verlag Minerva, Wolfratshausen, and contains an essay by Markus Brüderlin. 102 pages with 51 full-color plates .

The supplementary volume to the catalogue was published in a bilingual edition (German and English), followed at a later date by a French and Italian edition, by Verlag Minerva, Wolfratshausen. It contains detailed descriptions of approx. 25 works. 56 pages with 25 full-color plates.